Half-Hidden Histories is a blog series on the fascinating people, places, and things you probably didn’t learn about at school. During a brutally hard time in the world, this edition looks at a seminal moment of Black activism in the UK.

Frank Crichlow & The Mangrove Nine

Perhaps not as hidden as some of the other histories in this series, The Mangrove Nine are likely familiar to anyone alive in London during the 1960s and ’70s. Nonetheless, this watershed moment in UK Black history—and the remarkable individuals involved—never featured in my history lessons. Now more than ever, we need to be reminded of the power and community demonstrated when this group of Black people were put on trial, and left their mark on the history of civil rights.

Born in Trinidad in 1932, Frank Crichlow was among the first wave of post-war Caribbean immigrants to the UK, arriving in England shortly before his 21st birthday. Crichlow first lived in Paddington (where he later recollected he could go a week without seeing another black person). He was hard-working and multitalented, and had a hand in developing the Notting Hill Carnival after the traditions of his birthplace. After working for British Rail and starting a band named the Starlight Four, Crichlow went on to open two key venues in Notting Hill: the El Rio café in 1959, and the Mangrove restaurant in March 1968. Crichlow was known and respected for these safe spaces he created for the Black community in London, especially in the wake of Notting Hill’s 1958 race riots.

The Mangrove was a tangible upgrade from the Rio, a proper venue serving West Indian cuisine, which frequently had people queuing down the street to get in. The restaurant quickly attracted attention, both welcome and unwelcome. It was a hangout for Black creatives, intellectuals, and campaigners; it played host to celebrities such as Jimi Hendrix, Diana Ross, and Sammy Davis Jr. The Mangrove was also repeatedly raided—six times in its first year of business—allegedly in the search for drugs, despite Crichlow’s widely known anti-drug stance. None were ever found. Nevertheless, the constabulary of Notting Hill appeared to have it in for Crichlow, issuing a slew of petty fines to the restaurant for whatever they could (including dancing after 11pm).

In 1969, Crichlow made a complaint of unlawful discrimination to the Race Relations Board. And he was not the only one to speak out against the wider pattern of oppression against Black people in London—the Black community and its allies took to the street in protest in August 1970. A political statement from the organisers of the demonstration (which included Crichlow) was distributed to the Home Office, the Prime Minister, the leader of the opposition, and High Commissioners of Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana, and Barbados. It outlines their protest against constant police harassment of Black people in London, and the legal system that condones it. It notes that they as a community have made many complaints, and that they felt their protest necessary “as all other methods have failed to bring about any change.” Their call for justice is one which rings particularly loud and true given the current protests in America.

“I know it is because I am a black citizen of Britain that I am discriminated against.”

Frank Crichlow’s complaint, 1969

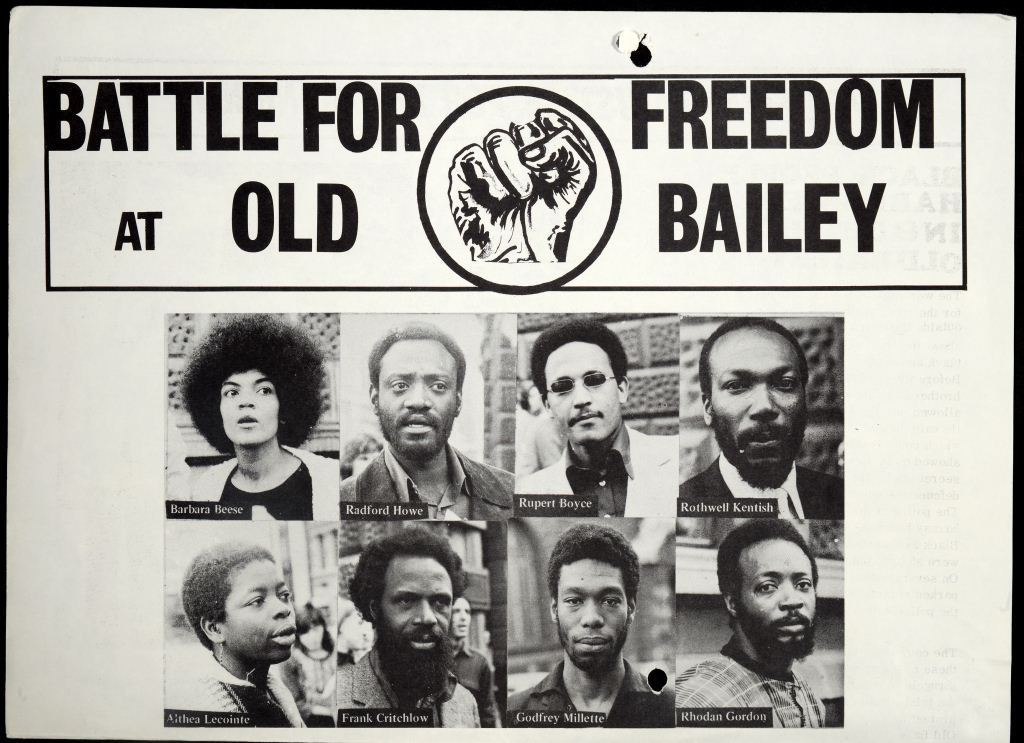

The march on Portnall Road was met with a hugely disproportionate response. When it began, 150 demonstrators were accompanied by 200 police. Violence erupted. Many were arrested. Nine people were charged with the primary charge of incitement to riot—they came to be known as the Mangrove Nine. They were Barbara Beese, Rupert Boyce, Frank Crichlow, Rhodan Gordan, Radford “Darcus” Howe, Anthony Innis, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Rothwell Kentish, and Godfrey Millett.

The trial, and the community support for those arrested, was huge for the Black Panther movement in the UK. The Nine radically (and unsuccessfully) applied for an all-Black jury, claiming this was trial by their peers as laid out in the Magna Carta. Howe and Jones-LeCointe even took the unusual step of acting as their own defence. The Nine’s trial lasted 55 days. The case became a public spectacle, with pickets organised outside the Old Bailey (where flyers like the one above would have been handed out).

As the case progressed, the attention turned on allegations of racism and brutality in the Metropolitan Police. All nine were eventually cleared of the main charge of inciting riot. The judge determined that the trial had shown “evidence of racial hatred on both sides”—a statement the Met Police tried, and failed, to have withdrawn.

The trial of the Mangrove Nine witnessed the first formal recognition of racism and prejudice within the police force. Its publicity and outcome inspired a number of other civil rights activists, and ultimately led to the government overhauling procedures relating to jury selection (a total of 63 candidate jurors had been rejected for the case before two Black jurors were impanelled). After his acquittal, Crichlow set up the Mangrove Community Association. This outreach programme was a lifeline for the local community: providing advice, working to improve housing, establishing facilities and services for the young and elderly, and helping to rehabilitate ex-offenders and addicts.

“It was a turning point for black people. It put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the black community.”

Frank Crichlow on the trial of the mangrove nine

The publicity of his trial and the public sway he held did not protect Frank Crichlow from future discrimination, however. In 1988, police officers armed with sledgehammers once again raided the Mangrove restaurant, once again claiming to be looking for drugs. Crichlow was brought into custody and remained there for five weeks. He was eventually granted bail, but under conditions that prevented him from going near his business for over a year. The Mangrove never recovered. The charges were thrown out and Crichlow later sued the Met Police in 1992 for false imprisonment, battery, and malicious prosecution. He was awarded damages of £50,000, a record at the time.

One of his solicitors remembered Frank as “a great person, never bitter… cool in the face of discrimination and prejudice.” His influence is still felt in Notting Hill’s yearly carnival, which he helped to develop in 1959 as a response to race riots and civil unrest in the area. A street festival which draws on Caribbean and Black diasporic cultures, it is today a hallmark of UK culture which attracts millions. The Mangrove does not survive, but the strength of the Mangrove Nine can (and should) be remembered forever.

References & Further Reading

Rights, resistance and racism: the story of the Mangrove Nine – an article from The National Archives which tells the story in conjunction with original objects held in their collections

Let’s talk about the Mangrove Nine – a blog from The National Archives, centred on a youth workshop which featured the Nine as a primary focus

Frank Crichlow obituary – authored by Margaret Busby for The Guardian

Celebrating the Mangrove – brief Channel 4 feature on the Mangrove Nine, 50 years on

One thought on “Half-Hidden Histories: The Mangrove Nine”